Security is Everyone's Business: From CEO to Developer

Passionate and curious about the world of security in our IT projects — especially on iOS and macOS — I'm also deeply concerned to see, almost every week, announcements of X million user data records hacked and released into the wild. And to observe a kind of ostrich policy: we punish, we impose fines, and meanwhile the sensitive data remains in the wild forever. This shouldn't happen anymore.

I'm not a cybersecurity expert, nor a cryptography specialist. Just someone who feels concerned, challenged, with a great thirst to learn about these subjects — digging into frameworks, understanding standards, and seeing how we can implement them in our projects by involving everyone.

This article represents only my views. Like everyone, I'm human, I can be wrong. I'm very open to feedback to improve, learn, but also to correct and enrich this article over time.

In 2024, the personal data of several million French citizens was exposed. In project teams, we still hear "security is for V2".

This article is for everyone building digital products: executives, product managers, designers, developers, QA, DevOps. It addresses work organization and team culture as much as technical design. Because security is everyone's business, and "I didn't know" is no longer an acceptable defense.

The Painful Reality

Let's start with the numbers. Not the ones we casually read in tech press, but those that directly concern French citizens, their data, their privacy.

2024-2026: The French Data Hemorrhage

In January 2024, third-party payer operators Viamedis and Almerys suffered a cyberattack. According to the CNIL, 33 million people had their health data exposed — civil status, date of birth, social security number, insurer name, contract guarantees. That's nearly one in two French citizens.

Two months later, in March 2024, it was France Travail's turn. According to the CNIL investigation, 43 million people were potentially affected — all current registrants and those from the past 20 years. Name, first name, date of birth, France Travail identifier, phone numbers, email and postal addresses.

In October 2024, Free announced a massive leak: 19 million subscribers and 5 million IBANs. In November, Auchan revealed 550,000 affected customers — then again in August 2025 with another leak. In January 2026, according to ZATAZ, URSSAF confirmed the exposure of data from 12 million employees who had been hired in the past three years.

And between these major incidents? Cultura with 1.5 million customers, Boulanger, Kiabi, La Poste, MAIF, BPCE through their provider Harvest, the Ministry of the Interior, the Ministry of Sports, the French Football Federation...

Statistically, your personal data is already circulating somewhere.

Exploding Costs

The IBM Cost of a Data Breach 2024 report lays out the numbers: the global average cost of a data breach reaches $4.88 million — a 10% increase in one year, the largest since the pandemic. For the healthcare sector, it exceeds $10 million. For finance, $6 million.

And detection time? Still according to IBM, on average 168 days to identify a breach, then 64 days to contain it. Six months during which attackers roam through your systems.

But perhaps the most telling is the economics of prevention:

- $1 invested in design to secure a feature

- $100 in development to fix an identified vulnerability

- $10,000 (or more) in production to handle a crisis

Europe Strikes Hard

Regulators are no longer looking away. According to the DLA Piper GDPR Survey of January 2025, since GDPR came into effect in 2018, cumulative sanctions exceed 5.88 billion euros in Europe.

The record? 1.2 billion euros imposed on Meta in 2023 by the Irish DPC for its EU-US data transfers. Behind: Amazon with 746 million in Luxembourg, TikTok with 530 million in 2025 for transfers to China, Instagram with 405 million for minors' data, LinkedIn with 310 million, Uber with 290 million in the Netherlands.

In France, according to the CNIL's 2024 report, 87 sanctions were issued for a total of 55 million euros. FREE just received 42 million euros in January 2026. NEXPUBLICA: 1.7 million for "insufficient security measures" in their software. MOBIUS, Deezer's subcontractor: 1 million euros. Yes, subcontractors pay too.

And these are just administrative fines. The French Penal Code (articles 226-16 to 226-24) provides for up to 5 years imprisonment and 300,000 euros in fines for executives in case of serious breach.

The Mirror Question

Before continuing, a question:

“On my last project, when did we talk about security? During the kick-off? Sprint planning? Never?”

If the answer is "never" or "vaguely at the end of the project," this article is for you.

Security is a Foundation, Not a Layer

The Analogy That Says It All

You don't build a house, then add the foundation. You don't dig the foundation "in V2." You don't say "for now we'll put the walls directly on the ground, we'll see later about stability."

Yet that's exactly what we do with security in many digital projects.

Security is not a feature you add. It's not a technical layer you plug in at the end of development. It's not an audit you commission before going live to "validate" what was done.

Security is the foundation. It conditions everything you can build on top. It defines architectural choices, usable technologies, possible data flows, permitted interactions.

What This Changes in Practice

When security is thought of as a foundation:

Architecture is drawn differently. You don't ask "how do I implement this feature?" but "how do I implement this feature securely?" The two questions don't have the same answers.

Certain choices become mandatory. Storing tokens? Keychain required, not UserDefaults. Calling a sensitive API? Certificate pinning, no blind trust. Handling health data? End-to-end encryption, not "we'll see."

Budget and timelines include these constraints. You don't discover at the end of a sprint that you need "three more days to secure." It's budgeted from the start, like accessibility, like testing.

The POC That Becomes Production

How many times have you heard — or said — these phrases?

- "It's just a POC, we don't do security"

- "We only have 100 users, no one's going to attack us"

- "We'll refactor when we have time"

- "Security is for V2"

The problem: the POC becomes V1. The 100 users become 100,000. The time to refactor never comes. And V2... V2 adds features on the shaky foundation of V1.

Result: security technical debt accumulates, vulnerabilities multiply, and one day, the incident. With this terrible phrase in the crisis meeting: "We knew it was fragile, but we never had time to consolidate."

Foundations Before Walls

A project with solid security foundations has:

- An architecture that clearly separates sensitive data

- Technology choices that don't compromise security for convenience

- Documented and controlled data flows

- Robust authentication mechanisms from day 1

- A coherent encryption strategy

- Logs that enable anomaly detection

It's not "more work." It's work done at the right time. Because redoing the foundation of an already-built building costs infinitely more than doing it correctly from the start.

2024-2026: The Time of Lost Illusions

The Size Illusion

"We're a small company, hackers go after the big ones."

False. Automated attacks don't discriminate. Bots constantly scan, looking for known vulnerabilities, exploiting default configurations. Your 10-person startup is as much a target as a large corporation — you just don't have the same defensive resources.

According to a study on 48 cyber incidents at unlisted French companies between 2017 and 2021, the risk of failure increases by about 50% in the 6 months following the announcement of an incident.

Clermont Pièces, an SME specializing in appliance parts, had to close in 2017 after a cyberattack destroyed their strategic data — customer files, production history, accounting data. Everything lost, company liquidated.

Lise Charmel, a lingerie manufacturer, placed in receivership in February 2020 after a ransomware attack. Camaïeu, already weakened, finished off by a cyberattack before its 2022 liquidation. Octave, a software publisher, liquidated in March 2025 after an attack in August 2024.

The Obscurity Illusion

"Our app isn't well-known, no one's going to target it."

Attackers don't target well-known apps. They target vulnerabilities. If your API has an SQL injection, it will be found and exploited whether you have 100 or 100,000 users. Scanning tools are automated, free, and run 24/7.

The Store Illusion

"Apple/Google check everything, if the app is on the store it's secure."

No. Store reviews check guideline compliance: no prohibited content, no obvious crashes, proper use of public APIs. They don't audit your business code security.

Your authentication logic? Not checked. Your token storage? Not checked. Your API calls? Not checked. Your certificate validation? Not checked.

Your code, your data, your responsibility.

The Magic Encryption Illusion

"We use HTTPS, it's secure."

HTTPS protects data in transit. It's necessary but very insufficient. It doesn't protect:

- Locally stored data (if it's in plain text)

- Authentication tokens (if poorly stored)

- Encryption keys (if they're in the code)

- Against man-in-the-middle attacks (if you don't do certificate pinning)

The Compliance Illusion

"We did a GDPR audit, we're compliant."

GDPR compliance is a legal obligation, not a security guarantee. You can have a perfect privacy policy, an impeccable processing register, a conscientious DPO... and a gaping hole in your code.

The CNIL penalizes documentary failures as much as technical ones. NEXPUBLICA got 1.7 million euros not for a missing document, but for "insufficient security measures" in their software.

Vibe Coding: When AI Codes and Nobody Understands

The 2024-2026 Phenomenon

A new way of coding has emerged. It's called "vibe coding" — asking an AI to generate code, seeing that it works, and integrating it into the project. No thorough review, no security analysis, no real understanding of what the code does.

"I asked ChatGPT to do my authentication." "Copilot generated the API call, it works." "I found the solution on Stack Overflow via AI, it's integrated."

The code works. On to the next ticket.

But who verified how the tokens are stored? Who validated that certificates are properly verified? Who reviewed the input validation logic? Who made sure the logs don't contain sensitive data?

The code is there, but it belongs to no one.

What AI Generates (and What We Don't Verify)

AI optimizes for "functional." It generates code that compiles, runs, produces the expected result. It doesn't optimize for "secure."

Here's what we regularly see in AI-generated code, copy-pasted without verification:

Tokens stored in plain text in UserDefaults:

UserDefaults is not encrypted. Any app with the right tools can read this data. Your user's authentication token is accessible.

HTTP requests without certificate validation:

This code disables SSL verification. Anyone on the same network can intercept the traffic.

Passwords hashed with MD5:

MD5 hasn't been considered secure since 2004. But AI keeps suggesting it because it's in its training dataset.

Hardcoded API keys:

This key will be extracted from the binary in minutes by anyone who knows how to use strings or a disassembler.

"It Works" ≠ "It's Secure"

This is the central phrase of this problem. The code works. Tests pass. The feature is delivered. The sprint is closed.

But "it works" has never meant "it's secure." Code can work perfectly while being a sieve.

AI doesn't know what it doesn't know. It doesn't know your business context, your regulatory constraints, the sensitivity of your data. It generates code that answers the question asked, not code that anticipates attacks.

And above all: the AI won't be in court if there's a leak. You will.

The Mirror Question for Every Developer

Before merging AI-generated code, ask yourself these questions:

“Where are secrets stored in this code? How are certificates validated? What do the logs contain in case of error? What data is transmitted, and how? Did I understand every line, or just observe that "it works"?”

If you can't answer these questions, you don't control this code. And code you don't control is code whose security you can't guarantee.

The Speed Culture: POC → Production With No Return

The Scenario We All Know

The context is always the same. A business opportunity, a tight deadline, a commercial promise already made.

Week 1: "We have three weeks to deliver the MVP. It needs to work for the client demo."

Week 2: "Great, the demo went well! The client wants the full version next month."

Week 3: "We don't have time to refactor, let's continue on this base."

Month 3: "We have 10,000 users now. We can't break everything to redo it properly."

Month 12: "We know it's fragile, but touching auth now is too risky."

Month 18: Security incident. Data breach.

The POC became V1. V1 became production. Production grew on POC foundations. And no one ever had "the time" to consolidate.

The Things We Tell Ourselves

"It's just a POC"

The POC has a planned lifespan of two weeks. It will still be in production three years later, with 50,000 users on it.

"We only have 100 users"

Today's 100 users will be 100,000 tomorrow. And the bad practices from the "100 users" era will still be there, exposed to 1000 times more risk.

"We'll refactor"

No one refactors. Ever. There's always a more urgent new feature, a new client to satisfy, a new deadline to meet. Security refactoring is systematically sacrificed on the altar of "later."

"No one's going to attack us"

Bots don't care about your size. They scan the entire internet, constantly, looking for known vulnerabilities. Your poorly secured little API will be found, indexed, exploited.

The Debt That Accumulates

Every security shortcut creates debt. And this debt has compound interest.

- Sprint 1: We store the token in UserDefaults "temporarily"

- Sprint 3: We add features that depend on this storage

- Sprint 6: We have 15 places reading this token

- Sprint 12: Migrating to Keychain would mean reviewing the whole architecture

- Sprint 18: The migration cost has become prohibitive

- Sprint 24: Data breach. The token was accessible.

With each sprint, the cost of correction increases. What would have taken an hour in sprint 1 takes a week in sprint 12 and a month in sprint 24.

And when the incident happens, you discover that the cost of not doing things correctly from the start far exceeds what you thought you were "saving."

Managers: Two Profiles, Two Responsibilities

Security isn't just a developer concern. Management decisions — deadlines, priorities, budgets — have a direct impact on a product's security posture.

And when facing these challenges, we encounter two very different manager profiles.

Profile 1: Good-Faith Ignorance

"I didn't know it was a problem."

This manager has a business, marketing, or product background. They're not technical, and that's normal — it's not their job. They trust the dev teams to "handle the technical stuff."

What they say:

- "It's technical, I trust you."

- "What matters is that it works for the client."

- "Security? That's IT's job, right?"

What they think (sincerely):

- "If it were really a problem, the devs would tell me."

- "Apple checks apps, so we're protected."

- "We have a firewall and antivirus, we're good."

This manager isn't malicious. They're simply untrained on cyber issues. No one ever explained to them that:

- Stores don't do security audits

- A firewall doesn't protect a mobile application

- "Trusting the devs" isn't enough if you don't give them time to secure

The solution:

- Mandatory basic training — not technical, just business and legal stakes

- Inclusion in design discussions, not just demos

- Systematic risk vulgarization in terms they understand: euros, reputation, legal sanctions

Mirror question for this profile:

“When did I last ask "and security-wise, where are we?" in a project meeting?”

Profile 2: Deliberate Ignorance

"I know, but my career comes first."

This manager is different. They know security is an issue. They've been warned — by a dev, by the DPO, by QA, by an audit. They understand the risks.

And they consciously choose to ignore them.

What they say:

- "We'll see that in V2." (which never comes)

- "The client wants the feature by Monday, period."

- "Don't worry, it's covered by the Terms of Service."

- "It's an acceptable risk."

What they think (without saying it):

- "I have my objectives to meet."

- "My promotion comes first."

- "If it leaks, it'll be the next person's problem."

- "Anyway, I'll be gone by then."

This is the "Me first, others aren't my problem" profile. Personal career takes precedence over user security, product longevity, collective responsibility.

What they don't realize:

The paper trail exists. The dev's email saying "warning, this isn't secure" is archived. The DPO's Slack alerting about GDPR risk is preserved. The meeting minutes mentioning "decision to ship despite technical team's reservations" can be exhumed.

Ignoring a documented alert is a characterized fault.

The Penal Code provides for personal executive liability. Case law shows that "I didn't know" is not a defense when it can be proven that you knew. And the proof is in your emails, your Slack, your Jira tickets.

Mirror question for this profile (brutal):

“If tomorrow there's a leak, will I be able to look my team in the eye and say I did what was necessary? Will I be able to explain to the judge why I ignored the March 15th alert?”

The Pressure of Deadlines: A System That Manufactures Vulnerabilities

The Vicious Circle

The problem isn't always an individual. It's often a system — an organization that structurally manufactures insecurity.

The answer: sprint after sprint, decision after decision, every time we chose deadline over security.

What Nobody Dares Say in Meetings

There are phrases that are almost never spoken:

- "This deadline is incompatible with secure implementation."

- "If we ship in two weeks, we ship with vulnerabilities."

- "I'd rather delay than deliver something dangerous."

- "No, we can't 'add security later'."

Why Nobody Says It

Fear of being "the one who blocks." In many organizations, raising a problem makes you responsible for the problem. Better to stay quiet and hope it passes.

The "yes man" culture. Saying yes is rewarded. Saying no is perceived as lack of commitment, agility, or solution-oriented thinking.

Precedent. Those who warned before were ignored, marginalized, sometimes pushed out. The message is clear: stay quiet and ship.

Lack of hierarchical support. Even if a dev or QA wants to warn, they know their manager won't support them against client or sales pressure.

What Should Happen

In a mature organization:

Alerts are heard, not punished. The dev who says "it's not secure" is a valuable alarm signal, not a roadblock.

Alerts are documented. In writing, tracked, timestamped. Not to cover yourself, but so the decision is made with full knowledge.

The decision is owned. If management decides to ship despite the alert, it's their responsibility, not the dev's. And this decision must be explicit, tracked, owned.

No "the dev coded it wrong" if the manager said "ship anyway." Responsibility lies at the decision level, not the execution level.

The Blame Game

Before the Incident

Before anything goes wrong, responsibility is fuzzy. Nobody really owns security because "it's everyone's job" — which in practice means it's no one's job.

The business side pushes for fast delivery. "The client needs this for next week." "The competition has already launched." "We'll lose the deal if we don't deliver."

Development does what it's asked. "The specs don't mention security." "We don't have time for that." "It wasn't in the estimate."

The CTO/Tech Lead tries to balance. "I'd like to do it right, but we have to ship." "We'll add security in the next sprint." "The priority is the demo."

Management validates the arbitration. "Ship now, secure later." "The business need prevails." "We'll manage."

Everyone contributes to degradation. No one feels responsible. Decisions are made without being documented. Alerts raised by developers are filed without follow-up. And the product goes live with its vulnerabilities.

Before vs After

| What We Say BEFORE the Incident | What We Say AFTER the Incident |

|---|---|

"Ship it, we'll see later" | "Why didn't anyone warn us?" |

"Security is for V2" | "It was obvious we needed to secure it" |

"Don't worry, it's just a POC" | "How did a POC end up in production?" |

"The dev handles the technical stuff" | "The dev should have refused to ship" |

"We don't have the budget" | "We should have prioritized" |

"It's an acceptable risk" | "Who decided it was acceptable?" |

The Constant

Responsibility always slides down the chain.

The sales rep who promised an unrealistic date? They've moved on. The manager who said "ship anyway"? They got promoted. The executive who didn't budget for security? They point to the technical team.

And it's the dev, the QA, the ops, who end up explaining why "they didn't do their job."

The Imaginary Tribunal

Imagine. Tomorrow, there's a data breach. You're summoned — by management, by lawyers, by the CNIL, by a judge.

What can you show?

- A warning email you sent... that was ignored?

- Meeting minutes where you expressed your concerns?

- A documented decision, assumed at the right hierarchical level?

- Or just "I was told to ship" with no trace?

The difference between these situations is the difference between being a victim of a dysfunctional system and being co-responsible for negligence.

Document. Always.

The Security Workflow of a Feature

If security is a foundation, it must be present at every stage of feature development. Not just "at the dev level," but from design through UX to deployment.

Here's how each role can — and must — contribute to a product's security posture.

Step 1: Business / Stakeholders

The need always starts with a business request. A new market to address, a feature requested by customers, a commercial opportunity.

The reflex to have:

Before rushing into specs, ask a simple question:

“What sensitive data is involved in this feature?”

Personal data? Health data? Financial data? Location data? User behaviors?

What business must accept:

Security cost is part of the feature cost. It's not an optional surcharge you can "negotiate." It's like accessibility, like testing: it's part of the price of doing things correctly.

Alerts to raise:

- "This feature handles health data — we're subject to HDS constraints."

- "We'll store IBANs — we need end-to-end encryption."

- "This is minors' data — enhanced GDPR, specific design."

Mirror question for business:

“Do I know the nature of the data my feature will handle? Have I anticipated regulatory constraints?”

Step 2: Product Manager

The PM translates business needs into functional specifications. They write user stories, define acceptance criteria, prioritize the backlog.

The reflex to have:

Every user story that touches data must have security acceptance criteria, not just functional ones.

Example for a "Biometric login" feature:

What the PM must demand:

- A security estimate in addition to the dev estimate

- Threat identification before development

- Documented acceptance of residual risks

Mirror question for the PM:

“Do my user stories have security acceptance criteria? Who validates that they're met?”

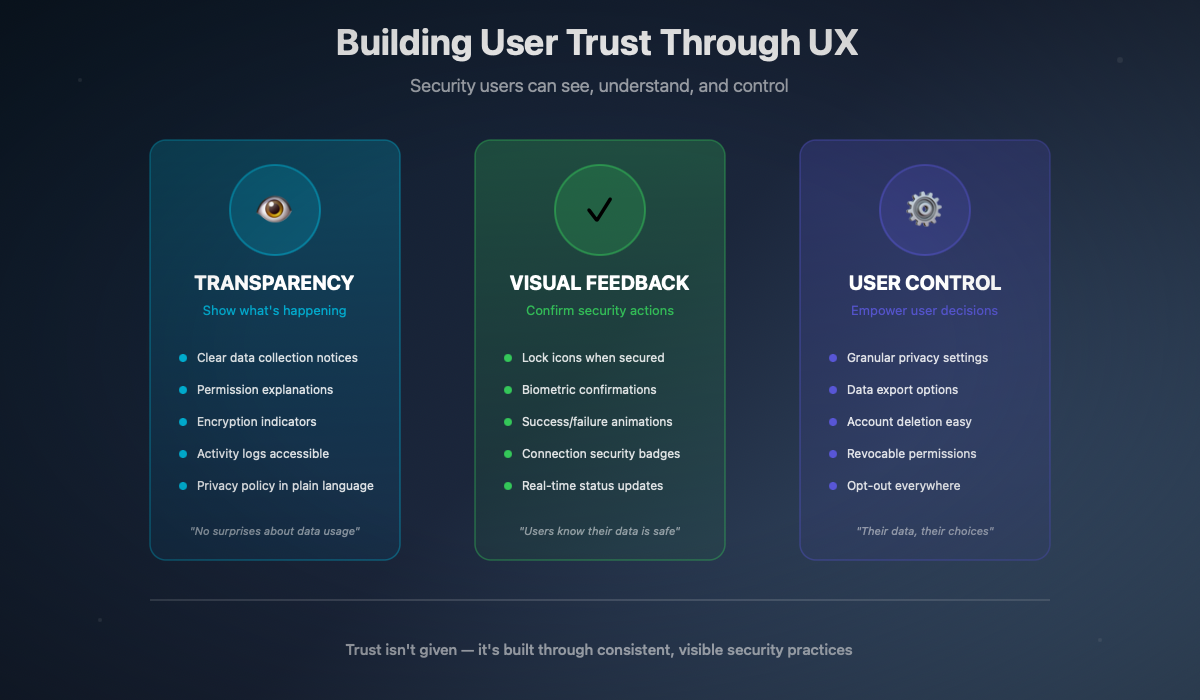

Step 3: UX/UI Designer

Design directly influences security. A poorly designed interface can make the user bypass protections, or not understand what's happening to their data.

The reflex to have:

Design security flows, not just happy paths. What happens when auth fails? When the user refuses permissions? When the session expires?

What the designer can contribute:

- Clear visual feedback on sensitive actions ("deleting your data", "sharing with third parties")

- Graduated confirmation on irreversible actions

- Transparency on data collection (what, why, for how long)

- Intuitive recovery flows (lost password, compromised account)

- Interfaces that don't push to skip security steps

Example of bad vs good design:

| Bad Design | Good Design |

|---|---|

"Skip" prominent on double auth | "Enable now" prominent, "Later" discrete |

Complex password buried in settings | Password change during onboarding if weak |

No feedback after sensitive action | Clear confirmation with details |

Hidden permissions request | Clear explanation before permission |

Mirror question for the designer:

“Does my design make security the path of least resistance? Or does it encourage bypassing it?”

Step 4: Data Analyst / Data Scientist

Data is at the heart of security concerns. Those who handle it have a special responsibility.

The reflex to have:

Question every data collection. Do we really need it? For how long? In what form?

Data minimization principles:

- Only collect what's strictly necessary

- Anonymize when precise identification isn't needed

- Pseudonymize when temporary linking is needed

- Delete when the original purpose is fulfilled

- Encrypt when storage is necessary

What the data person must demand:

- Documented legal basis for each collection

- Defined and enforced retention period

- Secure deletion procedure

- Restricted access to sensitive data

Mirror question for the data analyst:

“For each piece of data I collect: why this one? For how long? Who has access? What if it leaks?”

Step 5: Developer

The developer implements. But they're also often the last bulwark against a bad decision.

The reflex to have:

Not just ask "how to implement" but "how to implement securely." Challenge specs that create vulnerabilities.

Non-negotiable technical points:

- Secrets in Keychain, not UserDefaults

- Certificate pinning on sensitive APIs

- Input validation everywhere (client AND server)

- Encrypted logs without sensitive data

- Hardening enabled in release builds

- Dependencies audited and up to date

What the developer must do:

- Raise alerts when they see a security issue

- Document these alerts in writing

- Refuse to implement something known to be dangerous (and document the refusal)

- Propose secure alternatives with their cost

Mirror question for the developer:

“If this code leaked, what would be exposed? Am I comfortable defending my implementation before a judge?”

Step 6: QA / Tester

QA doesn't just test that "it works." They also test that "it resists."

The reflex to have:

Add security test scenarios alongside functional tests.

Security test scenarios:

- Try to access a feature without authentication

- Inject unexpected data in fields (SQL, XSS, special characters)

- Try to replay a request with an expired token

- Verify logs don't contain sensitive data

- Test behavior with revoked certificate

- Try to access another user's data

What QA must demand:

- Documented security acceptance criteria

- Access to tools for basic security testing

- Time in the test plan for security tests

Mirror question for QA:

“Have I tested what happens when someone tries to misuse the feature?”

Step 7: DevOps / SRE

Infrastructure is the last line of defense. And often the first point of attack.

The reflex to have:

Every deployment must be secure by default. No "we'll secure later."

Non-negotiables:

- Secrets in a vault, not in code or environment variables

- Segmented networks (databases not publicly accessible)

- Forced TLS everywhere

- Regularly updated dependencies

- Configured and monitored security logs

- Documented and tested incident response plan

What DevOps must do:

- Automate security checks in CI/CD

- Monitor for security anomalies (unusual attempts, spikes in errors)

- Maintain disaster recovery procedure (backup, restore)

- Document the complete infrastructure

Mirror question for DevOps:

“If an attacker gets access to a server, how far can they go? Is our infrastructure a single domino or compartmentalized blocks?”

Step 8: CIO / CISO

The IT/Security department sets the framework. But a framework that's not understood or applied is useless.

The reflex to have:

Create usable security policies, not just compliant ones.

What the CIO/CISO must provide:

- Clear, understandable, applicable security policies

- Adapted tools (not VPN for everything for everyone)

- Regular training, not just annual checkbox compliance

- An easy way to report security issues

- Involvement in projects from design, not at the end

What the CIO/CISO must avoid:

- Policies so restrictive they're systematically bypassed

- Blame without support when there's an incident

- Total disconnection from operational reality

- "Security theater" (measures that give the appearance of security without the substance)

Mirror question for the CIO:

“Are my security policies followed because they're understood and integrated, or systematically bypassed because they're impractical?”

Concrete Example: In-app Payment Feature

Here's how an "In-app payment" feature should go through these steps:

Business: "We want to enable in-app credit purchases." → Alert: Banking data = PCI-DSS, strong constraints.

Product: Specs with security criteria: card tokenization, no local storage of card numbers. → Estimate includes time for secure implementation.

UX: Journey with security feedback: "Payment secured by [provider]", visual indicators. → Dispute journey and payment method deletion journey.

Dev: Implementation via Apple Pay / certified provider, no direct card number handling. → Keychain for tokens, certificate pinning on calls.

QA: Injection tests, transaction replay attempts, behavior with declined card. → Testing payment token expiration.

DevOps: Provider secrets in vault, monitoring of abnormal transactions. → Alerts if unusual pattern (potential fraud).

Each step has its checkpoints. None is optional.

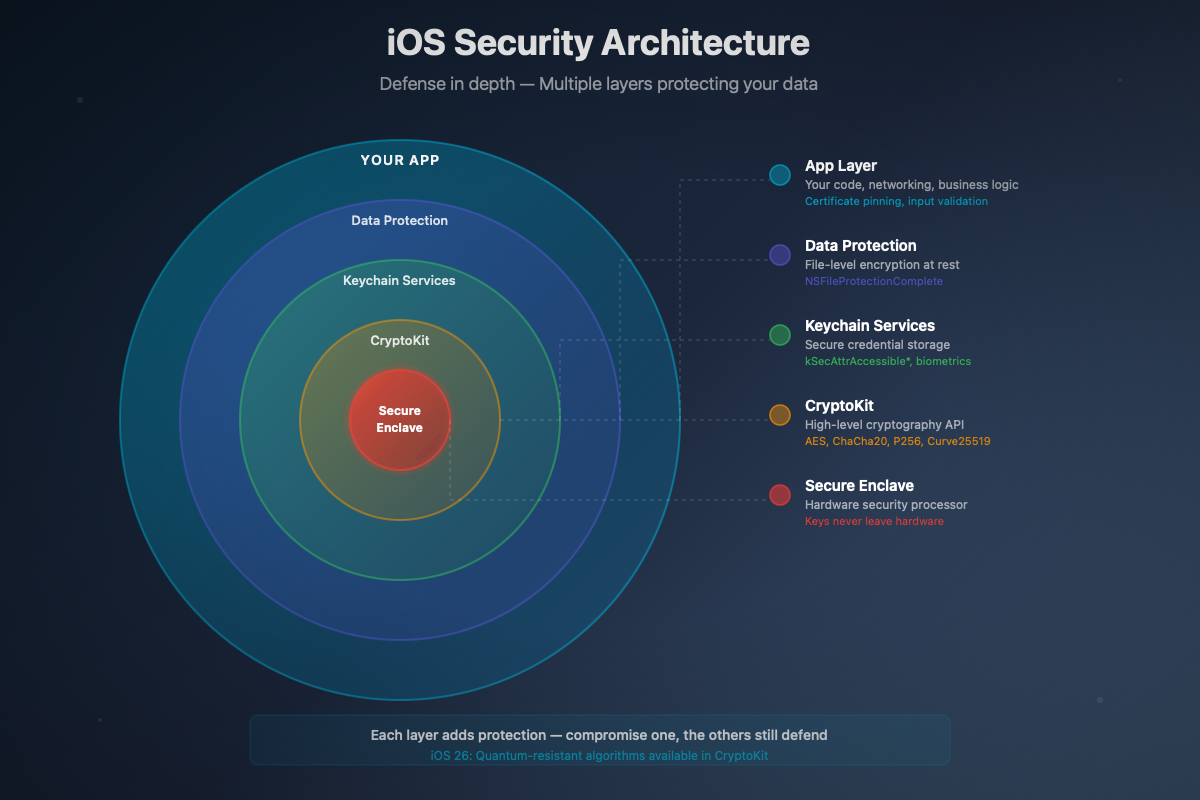

iOS Mobile Focus: Technical Specifics

This section is particularly for iOS developers, but the concepts are transferable to other platforms. This is my area of expertise — where I see good and bad practices daily.

The following sections will be developed in depth in dedicated technical articles. Here, the goal is to lay the foundation and raise awareness about what really matters.

Secure Storage: Keychain, Not UserDefaults

This is the basics. And yet, it's the most common mistake we see.

UserDefaults: what it really is

UserDefaults is user preference storage. Convenient, easy to use, ideal for storing "the user prefers dark mode" or "last sync date."

But UserDefaults:

- Is not encrypted

- Is accessible by debug tools

- Can be extracted from an unencrypted iTunes backup

- Is not protected if the device is jailbroken

What we find when auditing apps:

- Authentication tokens

- User identifiers

- API keys

- Personal data (email, name, sensitive preferences)

All this, in plain text, readable by any analysis tool.

Keychain: the iOS vault

Keychain is designed to store secrets. It is:

- Encrypted by the system

- Protected by Secure Enclave on modern devices

- Isolated between applications (except explicit Keychain sharing)

- Protectable by ACL (biometrics, device passcode, etc.)

The correct implementation:

Keychain protection levels:

| Attribute | Meaning |

|---|---|

| Accessible when device is unlocked |

| Same + not included in backups |

| Accessible after first unlock since boot |

| Only if a passcode is configured |

Golden rule: ThisDeviceOnly for everything sensitive. It prevents migration of secrets to another device via backup.

Data Protection: Encrypting at Rest

iOS offers file encryption built into the system. But you have to use it correctly.

Protection levels:

| Level | Protection |

|---|---|

| File encrypted when device locked |

| Remains accessible if opened before locking |

| Accessible after first unlock (default) |

| No additional protection |

Usage:

Warning: Many apps use the default level (completeUntilFirstUserAuthentication), which means data is accessible as long as the phone has been unlocked once since boot. For truly sensitive data, use .completeFileProtection.

Certificate Pinning: Never Trust Blindly

HTTPS is good. HTTPS with certificate pinning is better.

The problem with HTTPS alone:

A man-in-the-middle attacker can install their own certificate on the device (via malicious profile, compromised corporate network, etc.) and intercept all traffic. The application sees a "valid" certificate and trusts it.

The solution — Certificate Pinning:

The application only accepts specific certificates (or public keys) that you've embedded or explicitly validated. Any other certificate, even "valid," is rejected.

When to pin:

- Authentication APIs

- Payment APIs

- Sensitive data APIs

- Any exchange where a MITM would be critical

When not to pin:

- Non-sensitive public content

- Third-party CDNs (they manage their own rotation)

- When you can't control rotation (pinning requires updates when certificates change)

Post-Quantum Cryptography: Preparing for Tomorrow

Quantum computers threaten current cryptographic algorithms. It's no longer science fiction — it's a question of "when," not "if."

What's threatened:

- RSA, ECC: current asymmetric algorithms

- Signatures, key exchanges

What resists:

- AES 256: remains secure (but AES 128 becomes fragile)

- SHA-256, SHA-3: remain secure

What Apple shipped with iOS 26:

- iOS 17 had introduced PQ3 support for iMessage

- iOS 26 now integrates post-quantum algorithms in CryptoKit: ML-KEM (Kyber) for key encapsulation and ML-DSA (Dilithium) for signatures

- Secure Enclave now supports post-quantum keys

- The transition is underway — and it's time to prepare

What you can do now:

- Use AES-256 rather than AES-128

- Explore iOS 26's new CryptoKit APIs

- Design your systems so algorithms are interchangeable

- Don't hardcode cryptographic parameters

- Start testing post-quantum algorithms on your projects

For a complete technical deep dive on the new ML-KEM and ML-DSA algorithms, see our dedicated guide to post-quantum cryptography with iOS 26, published alongside this article.

iOS Security Checklist — The Vital Minimum

Before shipping an iOS app to production, verify these points:

If you can't check all these points, you have work to do before going to production.

Beyond Code: Organization and Team Culture

Previous sections addressed the technical aspects of security. But a secure product isn't built with good code alone — it's also built with good organization, adapted processes, and a team culture that values security.

The following sections address these organizational dimensions: the human factor (the primary cause of incidents), communication with users, and relationships between IT and business teams. This is no longer about technology — it's about management, corporate culture, change management.

The Human Factor: The First Vulnerability

Spoiler: it's almost never a genius hacker breaking through your technical defenses with sophisticated tools. It's almost always a human who clicks where they shouldn't, uses a weak password, or bypasses a procedure "to go faster."

The Real Causes of Incidents

According to the Verizon DBIR 2024, 68% of breaches involve a non-malicious human element — error, social engineering, misuse. We're not talking about malicious insiders, but simply people who make mistakes.

The most common vectors:

Phishing remains the number one entry point. A well-crafted email, a click on a malicious link, harvested credentials. All technical defenses can be bypassed if someone gives their password.

Weak or reused passwords. Despite years of awareness campaigns, "123456" remains among the most-used passwords. And password reuse means that one compromised service = access to all others.

Unpatched vulnerabilities. Not due to malice, but negligence or lack of time. "I'll update next week" becomes "it's been 6 months since the critical patch came out."

Misconfigurations. A publicly accessible S3 bucket, a database without a password, an admin interface exposed on the internet. Human errors in configuration.

"Shadow IT." Tools used without IT approval because "it's easier." Personal Google Drive to share files, unapproved Slack workspace, Excel with client data on a non-secured personal laptop.

Training Beyond Annual Compliance

The annual GDPR e-learning that everyone clicks through as fast as possible? Not effective. Security training must be:

Concrete: Not abstract theories, but real examples. "Here's a phishing email we received last month. Here's what would have happened if someone had clicked."

Regular: Not once a year, but continuous. Short reminders, timely alerts, updates on new threats.

Role-adapted: A developer doesn't have the same risks as an accountant. Training must be relevant to each person's daily work.

Non-punitive: The goal is to educate, not to punish. If someone makes a mistake, they should be able to report it without fear of sanctions. A reported mistake can be contained; a hidden mistake becomes a disaster.

Simulated: Controlled phishing exercises, intrusion tests, crisis simulations. Learn by practicing, not just by reading.

Creating a Reporting Culture

The biggest risk isn't that someone makes a mistake. It's that they hide it out of fear of consequences.

What to implement:

- Easy channel to report an incident (email, Slack, hotline)

- No sanctions for good-faith reporting

- Constructive feedback after each report

- Public recognition of valuable reports (anonymized if needed)

- Clear and known post-incident procedure

What to avoid:

- Publicly shaming someone who made a mistake

- Sanctions for honest errors

- Long and complex reporting processes

- Dismissing alerts with "it's nothing"

Mirror question for the whole organization:

“If an employee clicks on a phishing link today, do they immediately call IT or do they hide it and hope nothing happens?”

User Security Communication

Security isn't just a technical concern, it's also a communication concern. How do you talk to your users about security? How do you build trust without creating anxiety?

What Users Want to Know

Users aren't naive. They hear about data breaches, they worry about their privacy. But they don't want a technical course on cryptography.

They want to know:

- What data do you collect (and why)

- Who has access to this data

- How long you keep it

- What you do to protect it

- What happens if there's an incident

- How they can delete their data

They don't want:

- Jargon they don't understand

- 50-page policies nobody reads

- Promises that are too good to be true

- Silence in case of problems

Communicate Securely Without Creating Anxiety

Balancing is delicate. Too little communication = distrust. Too much = anxiety.

Best practices:

Progressive transparency: A simple summary accessible to everyone, with details available for those who want more. "Your data is encrypted" + a link to "How our encryption works" for the curious.

Positive but honest language: "We protect your data with banking-grade encryption" rather than "Your data could be hacked but we've taken measures." Without lying or exaggerating.

Concrete examples: "Your password never leaves your phone" is clearer than "We use client-side hashing for credentials."

Visible actions: Show what you do rather than saying it. "Connection from a new device? Alert sent. Unusual activity? Automatic block." User sees security in action.

Acknowledge uncertainties: "No system is infallible, but we do everything to protect you" is more credible than "100% secure."

What to Avoid

Promising the impossible:

- ❌ "100% secure"

- ❌ "Your data will never be compromised"

- ❌ "Unbreakable security"

No one can guarantee that. And if you promise it, you create an expectation you can't meet.

Hiding incidents:

GDPR requires notification of breaches to the CNIL within 72 hours and to affected individuals if the risk is high. Article 33 GDPR But beyond the legal obligation, transparency in case of an incident preserves long-term trust.

Companies that communicated quickly and honestly about their incidents generally preserved their reputation better than those that tried to minimize or hide.

Complicating to give the illusion of security:

Adding unnecessary steps doesn't secure, it frustrates. A CAPTCHA at every login doesn't protect better than a good authentication system. A double email confirmation doesn't add security, just friction.

Effective security is often invisible to the user. It's encryption in the background, server-side validation, anomaly monitoring — not repeated confirmation screens.

When IT Doesn't Understand the Business

There's a particular case that deserves attention: when security measures are imposed without understanding business workflows, they create more problems than they solve.

The "We Set Up a VPN" Syndrome

A scenario experienced in many organizations:

The decision: "To secure access, everyone must use the corporate VPN for everything."

The reality:

- Xcode builds downloading dependencies take 3x longer

- CI/CD deployments regularly timeout

- Calls to test APIs are slow or fail

- Team productivity drops

The consequence:

- Devs find workarounds (mobile hotspot, parallel configs)

- Shadow IT explodes

- Actual security decreases because practices become opaque

- Frustration and loss of trust in IT

VPN Is Not a Universal Solution

A VPN protects network traffic by routing it through an encrypted tunnel to the corporate network. It's useful for:

- Accessing internal resources from outside

- Protecting traffic on untrusted networks (public WiFi)

It's not useful for:

- Securing a mobile application (it doesn't run in the VPN)

- Protecting locally stored data

- Preventing phishing

- Replacing a real application security strategy

Imposing a VPN for everything, all the time, without understanding use cases, is "security theater" — the illusion of security without the substance.

What Works Better

Zero Trust rather than blind VPN:

The Zero Trust approach assumes no connection is trusted by default, even from the internal network. Each access is verified:

- Strong user authentication

- Device verification (is it managed? up to date? compromised?)

- Minimum necessary access (least privilege)

- Continuous behavior monitoring

It's more granular, better suited to modern uses (cloud, remote, BYOD), and less intrusive day-to-day.

Intelligent segmentation:

Not everything needs the same level of protection:

- Access to source code: strong protection, enhanced authentication

- Access to public documentation: basic authentication is enough

- Access to communication tools: depends on exchange sensitivity

Dialogue with teams:

Before imposing a measure, ask:

- What's your current workflow?

- What already slows you down?

- What tools do you use daily?

- How will this measure impact your work?

Mirror Questions for IT

“Do I know the real workflows of the teams I'm supposed to protect? Have I tested my measures in their day-to-day conditions?”

What the Law Says (And It Stings)

Data security isn't just a best practice. It's a legal obligation, with real sanctions for those who don't comply.

GDPR: The Big Picture

The General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), in effect since May 2018, requires Full GDPR text:

For any organization processing personal data:

- Minimization: only collect what's necessary

- Purpose: use data only for what was announced

- Limited retention: don't keep data indefinitely

- Security: implement appropriate technical and organizational measures

- Notification: report in case of breach (CNIL within 72h, affected individuals if high risk)

Possible sanctions:

- Up to 20 million euros or 4% of annual global turnover Article 83 GDPR

- Publication of the sanction (reputational damage)

- Compliance orders with penalty payments

Personal Executive Liability

Beyond sanctions against the company, the French Penal Code provides for personal sanctions.

Articles 226-16 to 226-24 of the Penal Code Légifrance text:

- Fraudulent data collection: 5 years imprisonment, €300,000 fine

- Processing without security measures: 5 years, €300,000

- Excessive retention: 5 years, €300,000

- Purpose diversion: 5 years, €300,000

These sanctions target responsible individuals, not just the company.

Who Is Responsible?

The executive: As legal representative, the executive is responsible for their organization's compliance. They cannot delegate this fundamental responsibility, even if they can delegate certain tasks.

What personally engages the executive:

- Ignoring DPO alerts

- Not budgeting for necessary security measures

- Making the decision to ship despite documented security reservations

The DPO: The Data Protection Officer advises, informs, controls. But they don't decide. The CNIL and EDPB (European Data Protection Board) are clear: the DPO is not responsible in case of non-compliance.

The executive makes the decisions, they bear responsibility.

The subcontractor: GDPR also holds subcontractors accountable. MOBIUS, Deezer's subcontractor, was fined 1 million euros. Source CNIL The subcontractor who doesn't properly secure entrusted data bears their own responsibility.

The NIS 2 Directive: Tightening Regulations

The NIS 2 directive (Network and Information Security), transposed into French law, expands and strengthens cybersecurity obligations. Source ANSSI

What changes:

- More organizations covered (essential and important sectors)

- Enhanced security obligations

- Incident notification within 24h (initial alert) then 72h (report)

- Personal executive liability explicitly mentioned

Article 20 of NIS 2: Member States shall ensure that the management bodies of essential and important entities may be held responsible for non-compliance.

In other words: executives can be personally prosecuted for their organization's cybersecurity failures.

"I Didn't Know" Is Not a Defense

Case law is clear: ignorance doesn't exonerate.

What matters:

- Were alerts issued? By whom? When?

- Were resources allocated?

- Were known best practices applied?

- The CNIL and ANSSI publish free guides — not following them is hard to justify

What aggravates:

- Documented alerts ignored

- Conscious choice not to secure for cost or deadline reasons

- Repeat offense after a first incident

The Sanctions That Speak

In France (2024-2026):

- FREE: 42 million euros — data breach Source CNIL

- NEXPUBLICA: 1.7 million — insufficient software security Source CNIL

- MOBIUS (subcontractor): 1 million — Deezer data breach Source CNIL

- DEDALUS Biologie: 1.5 million — medical data leak of 500k people Source CNIL

- KASPR: 240,000€ — LinkedIn collection without consent Source CNIL

In Europe:

- Meta: 1.2 billion euros — EU-US transfers Source DPC Ireland

- TikTok: 530 million — transfers to China Source DPC Ireland

- Amazon: 746 million — data processing Source CNPD Luxembourg

- LinkedIn: 310 million — behavioral analysis Source DPC Ireland

- Uber: 290 million — driver data transfers Source AP Netherlands

Total cumulative GDPR since 2018: 5.88 billion euros. DLA Piper GDPR Survey January 2025

Pragmatic Checklist by Role

Theory is good. Practice is better. Here's what each role can do starting Monday morning to improve their organization's security posture.

These checklists aren't exhaustive — they're a starting point, the vital minimum to begin integrating security into daily work.

CEO / Management / Executive Committee

You define priorities, budgets, corporate culture. Your role is crucial.

Key question:

“If tomorrow we suffer a data breach, will I be able to demonstrate that we had taken reasonable measures?”

Product Manager

You define what we build. Security starts in the specs.

Developer

You implement. And you're often the last line of defense.

QA / Tester

DevOps / SRE

Conclusion: Everyone's Responsibility

This article is long. Deliberately so. Because security can't be summarized in a checklist or slogan.

The essential to remember:

Security is a foundation, not a layer. You don't add it at the end, you build on it from the start. Every day of delay increases the cost of correction exponentially.

It concerns everyone. From the CEO who sets priorities to the developer who implements, including the PM who specifies, the designer who designs, the QA who tests. No one can say "it's not my job."

"It works" ≠ "It's secure." Functional code can be a sieve. AI code that you don't understand is code whose security you can't guarantee.

Trace, document, escalate. When there's an incident, the difference between "we had done everything possible" and "we were negligent" often comes down to documentation.

The human factor is the first vulnerability. Training, culture, easy reporting — more important than all technical tools.

Regulations aren't suggestions. 5.88 billion euros in GDPR sanctions, up to 5 years in prison for executives. The price of negligence is clear.

Where to Start?

- Read the checklist for your role in this article. Identify what you're already doing and what you're not.

- Ask the mirror question at the next meeting. "On this feature, when did we talk about security?"

- Document an arbitration. Next time the deadline wins over security, write it down. Who decided, what was the identified risk.

- Suggest one improvement. Not ten. One. Something achievable, measurable, immediate.

- Talk about security regularly. Not just when there's an incident. Normalize the topic.

One last thing: no one is immune. The most advanced cybersecurity companies experience incidents. What makes the difference is:

- Preparation (having a plan before the incident)

- Detection (quickly identifying that something is happening)

- Response (contain, communicate, remediate)

- Learning (understand what happened, improve)

The goal isn't to be "invulnerable" — that's impossible. The goal is to be resilient: able to resist, detect, react, recover.

Further Reading: Technical Articles

This article lays the foundations, the vision, the stakes. But concrete implementation requires in-depth technical knowledge.

Already Available

CryptoKit & Post-Quantum Security with iOS 26

Our guide on iOS 26's new post-quantum cryptographic APIs was published alongside this article:

- New ML-KEM (Kyber) and ML-DSA (Dilithium) algorithms

- Integration with Secure Enclave

- Progressive migration from classical algorithms

- Complete Swift implementation examples

Coming Soon

CryptoKit: The Complete Guide (February)

Apple's native cryptographic API in depth:

- Symmetric (AES-GCM) and asymmetric (P-256, Curve25519) encryption

- Hash functions and HMAC

- Secure Enclave and hardware keys

- Best practices and pitfalls to avoid

Swift Audit Strategies (February)

A complete guide to Swift code auditing, including:

- Network Security: ATS and Certificate Pinning

- Performance audit and memory optimization

- Security and best practices

- Accessibility and compliance

Keychain & Security Framework: The Complete Guide

Everything you need to know about iOS secure storage:

- Keychain architecture and protection classes

- Robust implementation with modern Swift

- Keychain sharing between apps

- Access Control Lists and biometrics

- Migration from UserDefaults

- Testing and validation

mDL & Secure Digital Identity

Identity on mobile:

- ISO 18013-5 standard (Mobile Driving License)

- mDL security architecture

- iOS implementation with Apple APIs

- Sovereignty and privacy concerns

Resources and References

Official Sources

CNIL — cnil.fr — Sanctions, guides, recommendations

ANSSI — cyber.gouv.fr — Best practice guides, certifications

Apple Security Documentation — developer.apple.com/security

IBM Cost of a Data Breach Report — ibm.com/reports/data-breach

GDPR Enforcement Tracker — enforcementtracker.com

Technical Guides

OWASP Mobile Security Testing Guide — owasp.org/MASTG

Apple Platform Security — support.apple.com/guide/security

CryptoKit Documentation — developer.apple.com/documentation/cryptokit

News and Monitoring

Cybermalveillance.gouv.fr — cybermalveillance.gouv.fr — Alerts, advice and victim assistance

ZATAZ — zataz.com — French cybersecurity news

Le Monde Informatique — lemondeinformatique.fr/securite — Cybersecurity section

CERT-FR — cert.ssi.gouv.fr — Official security alerts (ANSSI)

Krebs on Security — krebsonsecurity.com — Cybersecurity investigations

A Final Word

If you've read this far, thank you. This article is long, dense, sometimes uncomfortable. That's intentional.

Security isn't a comfortable topic. It confronts us with our shortcuts, our compromises, our "we'll see later." It reminds us that our decisions have consequences — for our users, for our companies, for ourselves.

But it's also a fascinating topic. Because doing things well, building products that truly protect the people who use them, is rewarding. It's work well done.

So, starting Monday morning, ask yourself:

“What can I do, at my level, to improve the security of what we're building?”

The answer exists. It's in the checklists above. It's in the mirror questions in this article. It's in the courage to say "no, we can't ship this as is."

Enjoy the upcoming technical articles. And good luck securing your projects.

This article is part of a series on mobile application security. Find all articles on the Atelier Socle blog.

Questions, comments, feedback? Contact us through the website form or on LinkedIn.